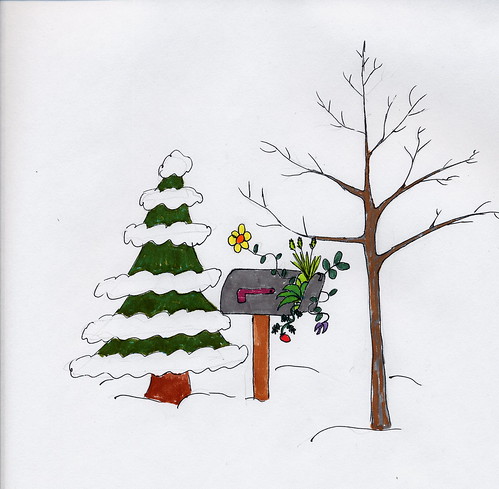

My drawing yesterday was a happy image of how getting packages of seeds is like having a mailbox full of plants in the middle of winter.

This is the reality of my current seed situation:

Yes, this is a real, non-staged shot of my dining room table as I tried to sort through what seeds to direct sow, which to start early inside... this is AFTER I removed a dozen or so packets I decided I wasn't going to have room for. I started counting them up... and gave up when I reached 100. I think I overdid it a bit. Just a bit.

30 January 2010

29 January 2010

28 January 2010

Gardening indoors: A much improved window

I'm all keen to get more house plants (even if, as my brother mentioned, this is more of a return to a former interest than anything entirely new) as you recall. So: I went to Van Atta's, our local good, basic (but not really inspired: They have nice, high quality plants but rarely any "I never knew that existed, but now I NEED it" plants) garden center, and looked at house plants. I came home with three: An unknown begonia, a Dracaena with freakishly awesome variegation ('Lemon Surprise' I am thinking, but possibly 'Lemon Lime') and Chlorophytum 'Fire Flash'

Here is the window before:

And After:

(I'm basing my before and after shots for this project on weight-loss advertisements. Before shots taken so as to maximize ugliness (at night, with the flash) and after shots taken to maximize prettiness (all back lit and glow-y).)

While I was trying to photograph it, Smudge decided to come "help"

He later knocked the chlorophytum over. Hopefully it is tough enough to take it, because I am utterly enamored by it. What a great shade of orange. I think I'll remove a lower leaf or two to show it off better. The only thing I have doubts about is the begonia -- most begonias are fussy, though some are also virtually impossible to kill. We'll see what class this one falls into. I also wonder if it will get enough light there, in front of the other two. If it starts looking miserable I'll have to track down a better dark-leaved plant for that spot.

27 January 2010

Wednesday Links

Linda Chalker-Scott at The Garden Professors rips to shreds the recently talked about (including, I'm a little embarrassed to admit, right here on my blog) paper about water droplets on sunny days causing leaf burn. The take home message is that watering on sunny days almost certainly doesn't harm anything. But go read it! Watching a good scientist tear apart lousy research is one of the best spectator sports ever! (Oh, sorry -- is my nerd showing?)

Another episode of: Plant breeders making plants uglier! This week: Proliferated roses as a cut flower. Ugh. I found this link on a comment thread over on the Rose hybridizers Association forum where people made comments like: "Very reminiscent of some hideous parasite or tumorous growth." and (my favorite): "Nothing says, "I just gave you scabies, dear," like a proliferated rose on a date."

I can't resist being all meta and fractal-like, so: Here is a link to another list of gardening links from the sunset fresh dirt blog!

From a trashy advice column in the UK, this complaint: "My cold, control freak husband loves his garden more than me." Uh oh. Wonder if my partner wrote that letter?

If you are interested in genetics, biotechnology and just what plant breeders do these days, check out this post from The Scientist Gardener. It is a good introduction to some of the cool tools breeders use these days.

I'm becoming kind of addicted to Deborah Silver's blog, Dirt Simple. For example, this post which is nothing but incredibly lovely flower arrangements in colors that make me drool... (And: Check out this!)

Another episode of: Plant breeders making plants uglier! This week: Proliferated roses as a cut flower. Ugh. I found this link on a comment thread over on the Rose hybridizers Association forum where people made comments like: "Very reminiscent of some hideous parasite or tumorous growth." and (my favorite): "Nothing says, "I just gave you scabies, dear," like a proliferated rose on a date."

I can't resist being all meta and fractal-like, so: Here is a link to another list of gardening links from the sunset fresh dirt blog!

From a trashy advice column in the UK, this complaint: "My cold, control freak husband loves his garden more than me." Uh oh. Wonder if my partner wrote that letter?

If you are interested in genetics, biotechnology and just what plant breeders do these days, check out this post from The Scientist Gardener. It is a good introduction to some of the cool tools breeders use these days.

I'm becoming kind of addicted to Deborah Silver's blog, Dirt Simple. For example, this post which is nothing but incredibly lovely flower arrangements in colors that make me drool... (And: Check out this!)

26 January 2010

Ewww...

The snow is starting to melt a little, and walking through the gardens at MSU I noticed the ornamental kale I had admired back in December.

Not looking so admirable now...Still alive, I give them that, but the lower leaves looking like used toilet paper isn't exactly appealing.

We'll see. I already ordered seeds for the variety Redbor, so I might as well grow it. If it turns hideous in January too, I can always rip it out.

Not looking so admirable now...Still alive, I give them that, but the lower leaves looking like used toilet paper isn't exactly appealing.

We'll see. I already ordered seeds for the variety Redbor, so I might as well grow it. If it turns hideous in January too, I can always rip it out.

25 January 2010

Therapy for winter: Meijer Gardens

So this weekend I went to Meijer Gardens -- a huge public greenhouse about an hours drive away in Grand Rapids. They were having their annual orchid show this weekend, which was additional reason to go.

They had LOTS of orchids. And lots of people selling orchids. My new Indoor Gardening resolution was burning in my mind, tempting me to buy, buy, buy... But I restrained myself. I simply looked, noticed what I liked, and asked the one orchid freak (and when I say orchid freak, I mean freak I asked him about slipper orchids and he launched into an explanation of how they're not REALLY orchids because their fertile anthers are derived from the wrong whirl. Right. Though I could, if prompted, launch into rant about how rosemary is actually a salvia due to THEIR anthers, so I guess I can't make fun of him) of my aquaintance what he would recommend for my house, which I keep very very cool.

Luckily, the first genus he mentioned is ALSO the genus I had been admiring most in the show: Masdevallia.

(Sorry about the bad photos -- it was dim, and the crowds made it hard to get good pictures -- check out google images for a better idea of how cool these orchids are)

But there weren't many for sale -- because, I guess, most people don't keep their house in the 50s and 60s all winter. So I'm going to read more, and then maybe order some from somewhere.

After the orchid show, we enjoyed the consevatories, as you can see in these photos. Starting with a shot of the arid room for the sake of Germi who is suffering from too much rain.

They had LOTS of orchids. And lots of people selling orchids. My new Indoor Gardening resolution was burning in my mind, tempting me to buy, buy, buy... But I restrained myself. I simply looked, noticed what I liked, and asked the one orchid freak (and when I say orchid freak, I mean freak I asked him about slipper orchids and he launched into an explanation of how they're not REALLY orchids because their fertile anthers are derived from the wrong whirl. Right. Though I could, if prompted, launch into rant about how rosemary is actually a salvia due to THEIR anthers, so I guess I can't make fun of him) of my aquaintance what he would recommend for my house, which I keep very very cool.

Luckily, the first genus he mentioned is ALSO the genus I had been admiring most in the show: Masdevallia.

But there weren't many for sale -- because, I guess, most people don't keep their house in the 50s and 60s all winter. So I'm going to read more, and then maybe order some from somewhere.

After the orchid show, we enjoyed the consevatories, as you can see in these photos. Starting with a shot of the arid room for the sake of Germi who is suffering from too much rain.

Warning: Slightly inapproriate behavior with an amorphophallus ahead:

A tillandsia of some sort:

23 January 2010

Gardening inside

Here is a time line of the events leading up to today's post. (photos are of most of the windows in my house. The reason for that will become apparent.)

1/15/2010: Carol, as always, hosts Bloom Day. Bloggers in cold areas everywhere complained they had no flowers because it was January and posted pictures of lampshades and chairs instead.

1/17/2010: Mr. Subjunctive posts a rant about the lack of winter blooms stating that: "Winter is not an excuse. It never was. Now go buy an African violet before February 15 or I will come to your blog and kick your ass."

1/20/2010, 8:16 am: I do my weekly "Wednesday Links" post, including a link to Mr. Subjunctive's rant, and make a sort of half-hearted promise to order a lazy cop-out collection of random winter flowering house plants.

1/20/2010, 9:17 am: Mr. Subjunctive comes to my blog and writes a comment. A very long comment. Actually, I think it is so long it technically qualifies as a guest post, in which he details some winter flowering house plants he does and does not recommend.

1/20/2010, 5:00 pm, heading home from work: Hit by a double dose of full strength Mr. Subjunctive, I finally start really thinking about his point and ask myself this question: Why DON'T I treat the inside of my house as just as much a garden as the outside?

1/20/2010, 7:00pm, after dinner: I start getting excited. Way too excited. I look at my pitiful windowsills (which basically are refugee camps for things from last years outdoor garden that I'm hoping will pull through until spring) and start having visions of lush, well-designed gardens of contrasting foliage textures and rich, fragrant displays of winter flowers.

1/20/2010, 9:00pm: I have filled several pages of my notebook with ideas for windowsill gardens. My list of plants to buy starts getting longer. I take "before" pictures of all the windows in the house. My long-suffering partner asks what on earth I am doing, and is subjected to a 20-minute exposition on my rapturous conversion to the cult of indoor gardening.

1/21/2010: I sit in my office at school supposedly writing a paper, but really googling things like: billbergia, trailing african violets and philodendron. I call my partner to tell him we're going to an orchid show this weekend.

So that is the story. I'm going nuts. I'm determined that next winter will be full of lovely and interesting things to post about and enjoy. We'll see how it turns out. By the way, Mr. S.: You need to make more lists. Specifically, I need a list of: House plants with frilly/ferny/fluffy foliage. Also: Plants with a viny, trailing, weepy growth habit. Not to mention: Plants with dark purple/red/maroon foliage. Oh! And things with fragrant flowers. Not to, like, tell you how to do your job or anything, but still. I'd like to see those lists.

1/15/2010: Carol, as always, hosts Bloom Day. Bloggers in cold areas everywhere complained they had no flowers because it was January and posted pictures of lampshades and chairs instead.

1/17/2010: Mr. Subjunctive posts a rant about the lack of winter blooms stating that: "Winter is not an excuse. It never was. Now go buy an African violet before February 15 or I will come to your blog and kick your ass."

1/20/2010, 8:16 am: I do my weekly "Wednesday Links" post, including a link to Mr. Subjunctive's rant, and make a sort of half-hearted promise to order a lazy cop-out collection of random winter flowering house plants.

1/20/2010, 9:17 am: Mr. Subjunctive comes to my blog and writes a comment. A very long comment. Actually, I think it is so long it technically qualifies as a guest post, in which he details some winter flowering house plants he does and does not recommend.

1/20/2010, 5:00 pm, heading home from work: Hit by a double dose of full strength Mr. Subjunctive, I finally start really thinking about his point and ask myself this question: Why DON'T I treat the inside of my house as just as much a garden as the outside?

1/20/2010, 9:00pm: I have filled several pages of my notebook with ideas for windowsill gardens. My list of plants to buy starts getting longer. I take "before" pictures of all the windows in the house. My long-suffering partner asks what on earth I am doing, and is subjected to a 20-minute exposition on my rapturous conversion to the cult of indoor gardening.

1/21/2010: I sit in my office at school supposedly writing a paper, but really googling things like: billbergia, trailing african violets and philodendron. I call my partner to tell him we're going to an orchid show this weekend.

So that is the story. I'm going nuts. I'm determined that next winter will be full of lovely and interesting things to post about and enjoy. We'll see how it turns out. By the way, Mr. S.: You need to make more lists. Specifically, I need a list of: House plants with frilly/ferny/fluffy foliage. Also: Plants with a viny, trailing, weepy growth habit. Not to mention: Plants with dark purple/red/maroon foliage. Oh! And things with fragrant flowers. Not to, like, tell you how to do your job or anything, but still. I'd like to see those lists.

22 January 2010

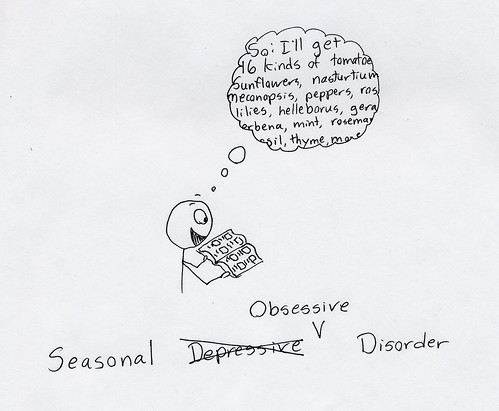

I blame it on the people whe keep sending me seed catalogs...

You've heard about people who get depressed by the short, dark days of winter.

I have a slightly different problem.

See my other garden drawings

21 January 2010

Trying in 2010: Wacked out zucchini

I love zucchini. Easy to grow and delicious -- what more could you want? And I thought I had found the perfect variety: For the past several years I've grown Costata Romanesco (as seen in this picture from Johnny's Selected Seeds) – the rich, nutty flavor and crisp texture put it in a class by itself. It is also beautiful, AND isn't so extreme when it comes to yield. Normal zucchini produce in gross excess. Costata Romanesco produces maybe half as much -- a far more manageable amount.

But: there is a problem with all the zucchini I've ever tried. Right when they are hitting their stride and producing away, a devilish little insect called the squash vine borer suddenly causes them to wilt, collapse, and die. These noxious little beasts don't eat the leaves like most insect pests – no, the larva burrow through and eat the stem, right at the base of the plant. In other words: They munch away at the one place where a little damage can kill the entire plant, bringing the zucchini harvest to a screeching halt. I've not seen any scientific studies on this, but personally I'm convinced the borers do this out of a twisted desire to ruin my summer. You can bet that if zucchini was a weed, they wouldn't be so eager to eat it. Rotten borers.

I hate squash vine borer. Either I spend most of the summer picking all their wretched little eggs off my plants, or they ruin my zucchini season half way through the summer. So I was excited this winter to learn that I may have an alternative. Zucchini (along with acorn, spaghetti, and delicata squash) is derived from the species Cucurbita pepo – a species that squash vine borers happen to adore. Cucurbita moschata, the species which produces butternut squash, however, is resistant to borers. Butternuts are one of my favorite winter squashes – delicious and sweet -- but they are hardly a replacement for zucchini. At least that is what I thought. This year I learned of a variety of C. moschata called Zucchetta rampicante tromboncino (picture from Washington State Extension) a long,

stretched out butternut intended to be eaten young, as a summer squash (though you can apparently eat at the end of the season as a winter squash too). Could this be it? A borer resistant zucchini? Well, we shall see.The reviews on Dave's Garden are overwhelmingly positive, though one person mentions a problem with borers! NO!!! I'm going to be growing it along with Costata Romanesco this year, comparing how they do with borers, and and putting them head-to-head in a taste test. Hopefully, the crazy new squash with the too long name will become my new favorite and I can kiss squash vine borers goodbye!

But: there is a problem with all the zucchini I've ever tried. Right when they are hitting their stride and producing away, a devilish little insect called the squash vine borer suddenly causes them to wilt, collapse, and die. These noxious little beasts don't eat the leaves like most insect pests – no, the larva burrow through and eat the stem, right at the base of the plant. In other words: They munch away at the one place where a little damage can kill the entire plant, bringing the zucchini harvest to a screeching halt. I've not seen any scientific studies on this, but personally I'm convinced the borers do this out of a twisted desire to ruin my summer. You can bet that if zucchini was a weed, they wouldn't be so eager to eat it. Rotten borers.

stretched out butternut intended to be eaten young, as a summer squash (though you can apparently eat at the end of the season as a winter squash too). Could this be it? A borer resistant zucchini? Well, we shall see.The reviews on Dave's Garden are overwhelmingly positive, though one person mentions a problem with borers! NO!!! I'm going to be growing it along with Costata Romanesco this year, comparing how they do with borers, and and putting them head-to-head in a taste test. Hopefully, the crazy new squash with the too long name will become my new favorite and I can kiss squash vine borers goodbye!

20 January 2010

Wednesday Links

Another great post from Deborah Silver over at Dirt Simple -- about container gardening. The post includes a series of photographs of a dizzying array of different designed in the very same set of containers. If you are looking for inspiration for your containers this year, start with this post!

Kinda off topic, but: I'm proud to be writing this on blogger now that google as finally taken a stand against censorship in China! Now we just need Yahoo, Microsoft, and all the rest to join them.

Mr. Subjunctive of PATSP writes forcefully of how EASY it is to have things blooming in the middle of winter. I feel humbled... My house plants generally consist of things I grew outside all winter and am trying to overwinter. I shall hereby go to www.glasshouseworks.com (my favorite wacked-out source for tropicals -- though I have to admit, the quality of plants from them can be pretty hit and miss) and order their winter blooming house plant collection -- because I really don't know diddly about house plants, and would rather let some crazy person in Ohio pick them out for me.

For all you Southern gardeners suffering through a harsh winter, The Patient Gardener makes a good point: Hard winters provide lots of valuable information about what is REALLY hardy. (I can say this with a smile on my face because here in Michigan we are having a remarkably mild winter, and I'm expecting all sorts of things to survive.)

Young people aren't going into horticulture -- at least in Southern Australia. I've not seen numbers for the US -- I wonder what the trend is here?

Bert Cregg, over at the Garden Professors (and just down the hall from me in real life) has a nice post suggesting alternatives to the over planted blue spruce. I've been thinking more about winter interest of late, so cool conifers on my list of things to get this spring.

Kinda off topic, but: I'm proud to be writing this on blogger now that google as finally taken a stand against censorship in China! Now we just need Yahoo, Microsoft, and all the rest to join them.

Mr. Subjunctive of PATSP writes forcefully of how EASY it is to have things blooming in the middle of winter. I feel humbled... My house plants generally consist of things I grew outside all winter and am trying to overwinter. I shall hereby go to www.glasshouseworks.com (my favorite wacked-out source for tropicals -- though I have to admit, the quality of plants from them can be pretty hit and miss) and order their winter blooming house plant collection -- because I really don't know diddly about house plants, and would rather let some crazy person in Ohio pick them out for me.

For all you Southern gardeners suffering through a harsh winter, The Patient Gardener makes a good point: Hard winters provide lots of valuable information about what is REALLY hardy. (I can say this with a smile on my face because here in Michigan we are having a remarkably mild winter, and I'm expecting all sorts of things to survive.)

Young people aren't going into horticulture -- at least in Southern Australia. I've not seen numbers for the US -- I wonder what the trend is here?

Bert Cregg, over at the Garden Professors (and just down the hall from me in real life) has a nice post suggesting alternatives to the over planted blue spruce. I've been thinking more about winter interest of late, so cool conifers on my list of things to get this spring.

19 January 2010

More evidence: Gardening is the next big thing

Guess where I took these images (sorry about the crappy quality -- low light, and lots of people make for difficult shooting):

Some kind of home and garden show? A plant geek event? Nope: Check out this one:

A cool little three wheeled thing surrounded by cyclamen? Yes folks, we're talking about The North American International Auto Show in Detroit. And it was jam packed with plants -- iris reticulata, tulips, daffodils, magnolias, cyclamin, boxwoods, taxus, forsythia.... Plants are officially going mainstream, people.

And thank goodness for that! I'm NOT a car person -- as in, I was 22 when I got my drivers license... took the test the same week I took the GRE for grad school. Aced the GRE. Almost failed the drivers test. Even now I bicycle if at all possible. My partner, on the other hand, built his first car from scrap when he was 15. So we went to the autoshow. The plants were the only thing that kept me awake!

Though I do have to admit, there were a couple cool cars: I loved this cute little all-electric pickup truck! Perfect for quick trips to the nursery.

And I begrudgingly admit that this car was pretty cool too... it also costs more than twice what I paid for my HOUSE.

Some kind of home and garden show? A plant geek event? Nope: Check out this one:

A cool little three wheeled thing surrounded by cyclamen? Yes folks, we're talking about The North American International Auto Show in Detroit. And it was jam packed with plants -- iris reticulata, tulips, daffodils, magnolias, cyclamin, boxwoods, taxus, forsythia.... Plants are officially going mainstream, people.

And thank goodness for that! I'm NOT a car person -- as in, I was 22 when I got my drivers license... took the test the same week I took the GRE for grad school. Aced the GRE. Almost failed the drivers test. Even now I bicycle if at all possible. My partner, on the other hand, built his first car from scrap when he was 15. So we went to the autoshow. The plants were the only thing that kept me awake!

Though I do have to admit, there were a couple cool cars: I loved this cute little all-electric pickup truck! Perfect for quick trips to the nursery.

And I begrudgingly admit that this car was pretty cool too... it also costs more than twice what I paid for my HOUSE.

18 January 2010

More about petunias

My petunias got a fair amount of comment when I posted a quick snapshot of the greenhouse full of them on bloom day, so I decided to scan, Ellis Hollow-style, some of the flowers so you can see more of what they look like.

First, at top left we have Petunia integrifolia (small, magenta, no scent) and at top right P. axillaris (large, white, extremely fragrant). Below are a selection of some of their grandchildren (aka: F2 generation) many of which are fragrant though are not. This is actually the hybrid that started it all back in the 1800s -- modern petunias are derived from the hybridization of these two species, with a lot more colors added, and most of the fragrance lost.

Next: At top left P. exserta (red, unscented), and at top right, P. axillaris again and below them, their grandchildren. P. exserta is a cool species because it is the only red, hummingbird pollinated petunia -- and it is nearly extinct. It was only discovered recently, and is only known in the wild in one tiny population of only about a dozen plants. Luckily, seeds have been collected and distributed, so these unique petunia can be preserved in greenhouses and gardens around the world. I like the clear pink colors of this hybrids a lot better than the magenta tones of the first... sadly, only a very few of them are scented.

By the way: If you are intrigued by these wild petunias, they are super easy to grow -- Select Seeds offers seeds of both P. axillaris and P. integrifolia. As far as I know, P. exserta is not commercially available, but if you want some, shoot me an e-mail (engeizuki at gmail dot com) and I can send you some. (UPDATE 7/6/2011: I am out of seed to share with people, however, I did send some seed to Annie's Annuals, and you can buy plants from.) It is an easy, self-sowing annual for me, and the hummingbirds love it.

And, if you are intrigued by the hybrids you can create them as well! It is SUPER easy: Step one: Take P. axillaris flower. Step two: Shove it into a P. integrifolia flower. Step three: harvest your hybrid seeds. Then you get the fun of growing up all the different types and picking your favorites to save seed from for next year, creating your own, unique strain of petunias.

First, at top left we have Petunia integrifolia (small, magenta, no scent) and at top right P. axillaris (large, white, extremely fragrant). Below are a selection of some of their grandchildren (aka: F2 generation) many of which are fragrant though are not. This is actually the hybrid that started it all back in the 1800s -- modern petunias are derived from the hybridization of these two species, with a lot more colors added, and most of the fragrance lost.

Next: At top left P. exserta (red, unscented), and at top right, P. axillaris again and below them, their grandchildren. P. exserta is a cool species because it is the only red, hummingbird pollinated petunia -- and it is nearly extinct. It was only discovered recently, and is only known in the wild in one tiny population of only about a dozen plants. Luckily, seeds have been collected and distributed, so these unique petunia can be preserved in greenhouses and gardens around the world. I like the clear pink colors of this hybrids a lot better than the magenta tones of the first... sadly, only a very few of them are scented.

By the way: If you are intrigued by these wild petunias, they are super easy to grow -- Select Seeds offers seeds of both P. axillaris and P. integrifolia. As far as I know, P. exserta is not commercially available, but if you want some, shoot me an e-mail (engeizuki at gmail dot com) and I can send you some. (UPDATE 7/6/2011: I am out of seed to share with people, however, I did send some seed to Annie's Annuals, and you can buy plants from.) It is an easy, self-sowing annual for me, and the hummingbirds love it.

And, if you are intrigued by the hybrids you can create them as well! It is SUPER easy: Step one: Take P. axillaris flower. Step two: Shove it into a P. integrifolia flower. Step three: harvest your hybrid seeds. Then you get the fun of growing up all the different types and picking your favorites to save seed from for next year, creating your own, unique strain of petunias.

16 January 2010

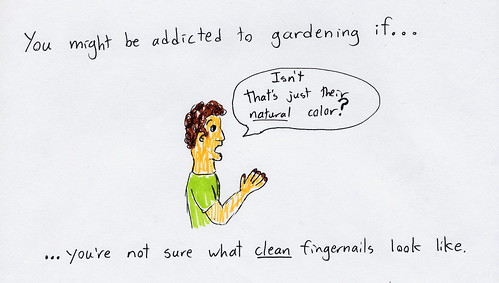

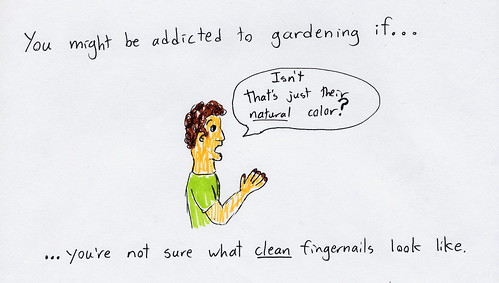

Gardener's fingernails

Don't think I need to make much of a comment on this drawing... if you are a gardener, you know what I'm talking about!

See my other garden drawings

15 January 2010

January Bloom Day

Once again, it is Bloom Day!

We have several inches of snow on the ground at the moment, so no chance of blooms outside (though the next few days are supposed to be warm, so I might see the ground this weekend!)

But inside I have paperwhites doing their pretty but stinky thing:

And at work I have a whole greenhouse full of petunias also doing a pretty but stinky thing

I'm working with wild petunias, some of which are incredibly smelly. Actually, they have a nice smell -- but this many of them in an enclosed space gets a little over powering!

And when I really need a break from winter, I wander over to the greenhouse next door, where my friend D is doing research on orchids:

Thank goodness for greenhouses! There are certainly good and bad things about being in grad school -- but the greenhouses are most decidedly one of the good ones!

We have several inches of snow on the ground at the moment, so no chance of blooms outside (though the next few days are supposed to be warm, so I might see the ground this weekend!)

But inside I have paperwhites doing their pretty but stinky thing:

And at work I have a whole greenhouse full of petunias also doing a pretty but stinky thing

I'm working with wild petunias, some of which are incredibly smelly. Actually, they have a nice smell -- but this many of them in an enclosed space gets a little over powering!

And when I really need a break from winter, I wander over to the greenhouse next door, where my friend D is doing research on orchids:

Thank goodness for greenhouses! There are certainly good and bad things about being in grad school -- but the greenhouses are most decidedly one of the good ones!

13 January 2010

And so another season of obsession begins...

Just SOME of the seeds I've ordered so far this year. I'm carefully NOT thinking about how on earth I'm going to have room for them all.

You gotta go check it out

One of my favorite bloggers, The Germinatrix, has stumbled on a revolting lair of (in her words) "unnecessarily pornographic" of stinkhorn mushrooms! It is insane. Seriously, you've got to go look at her post. You won't believe it.

Wednesday Links

MAT Kinase posts about a rumor to certify the entire state of Maine as organic. In his words, "an absolutely terrible idea" and I have to agree with him.

Holly Scoggins on The Garden Professors gives timely advice on what to do with poinsettias after Christmas: Throw them away! (She also has an amusing disclaimer relating to the fact that nothing will make you hate a plant as much as doing research on it. Something I well know... I used to be merely uninterested by petunias... now I loath the smelly, stinky, wretched things.)

A new hardy alstromeria cultivar from Cornel breeder Mark Bridgen is coming out this year! A fact I pass on because, a) alstromeria are cool, and b) I've met Mark Bridgen, and he is super cool.

Studio G passes along a link to lovely solar powered hanging lights for the garden... They look great -- perfect for trying to create that glowing Avatar-garden look I'm itching for this year!

Water droplets in the sun can burn plants Which is kinda cool, but who waters that way anyhow? Water on leaves is a no-no (promotes fungal diseases) and you should always water in the morning or evening to reduce loss by evaporation. But still: kinda cool -- theoretically, it could even start a fire!

Holly Scoggins on The Garden Professors gives timely advice on what to do with poinsettias after Christmas: Throw them away! (She also has an amusing disclaimer relating to the fact that nothing will make you hate a plant as much as doing research on it. Something I well know... I used to be merely uninterested by petunias... now I loath the smelly, stinky, wretched things.)

A new hardy alstromeria cultivar from Cornel breeder Mark Bridgen is coming out this year! A fact I pass on because, a) alstromeria are cool, and b) I've met Mark Bridgen, and he is super cool.

Studio G passes along a link to lovely solar powered hanging lights for the garden... They look great -- perfect for trying to create that glowing Avatar-garden look I'm itching for this year!

Water droplets in the sun can burn plants Which is kinda cool, but who waters that way anyhow? Water on leaves is a no-no (promotes fungal diseases) and you should always water in the morning or evening to reduce loss by evaporation. But still: kinda cool -- theoretically, it could even start a fire!

12 January 2010

Sign of the times: Vegetable seeds EVERYWHERE!

I was startled to see tomatoes for sale in Select Seeds, then White Flower Farm's catalog came, and it has vegetables on the cover AND devotes the first 5 pages to veg -- now High Country Gardens arrives and even THEY are offering "Chef selected vegetable seeds"! Good grief! Am I going to find vegetable seeds in the Plant Delights and Arrowhead Alpines catalogs too? Not that I've anything against vegetables -- I love growing vegetables -- but I get those from Johnny, Pinetree, Seed Savers etc... Select Seeds is for great fragrant plants, White Flower Farm is for gorgeous plant porn photography (though I've never ordered from them -- too expensive, and nothing that unique), and High Country Gardens is for making me wish I lived in a desert (but only ever so briefly) -- not cabages and tomatoes! I wonder, will the veg rage last?

(Addendum: Looked at this post shortly after pubishing it and -- my goodness! I corrected a LOT of typoes. I mean, my posts are always pretty liberally typo infested, but I think this set a new record.)

(Addendum: Looked at this post shortly after pubishing it and -- my goodness! I corrected a LOT of typoes. I mean, my posts are always pretty liberally typo infested, but I think this set a new record.)

11 January 2010

Trying this year: Determinate Tomatoes

I hate staking. I'll happily weed for hours on end, happy as can be. I'll spend a full day working hard with a shovel and smile all the while. But I hate staking.

Because of this, my tomatoes always end up sprawling in a tangled mess on the ground. I know they'll be healthier if I stake. I know it will be easier to harvest them if I stake. Because I know this, some years I actually go so far as to put stakes out in the garden, which resulted in my tomatoes being a wild mess with some stakes sticking out of the middle.

So this year, I'm going to try growing some determinate tomatoes.

The technical definitions of determinate and indeterminate just refer to where flowers are produced. Determinate plants produce them at the top of a stem, forcing new growth to come from new branches at the side of the plant, while indeterminate plants produce flowers along the sides of the stem, allowing a single branch to keep growing on and on and on.

This means that determinate tomatoes grow short and bushy -- rarely needing to be staked -- while indeterminate tomatoes grow long and floppy -- and theoretically ought to be staked, though of course I never actually do.

I've steered away from indeterminate tomatoes up until now, though, because catalogs always define them a different way: They say the determinate tomatoes produce fruit which ripens all at once, while indeterminate varieties produce continuously all summer long.

But: Recently I've been reading something different: Tom Clothier on the tomato page of his quirky, very enjoyable website, says some there are determinate tomatoes, which produce a load of fruit and then stop, and there are vigorous or strong determinates, which keep sending up new shoots, ending in flowers and fruit, all season -- so they produce continously like a indeterminate, but minus the staking, and are usually much earlier than indeterminates.

Which sounds perfect to me... We'll see! If I can get tomatoes which produce well and taste yummy but don't turn themselves into a tangled mass, I'm all for it. I'm still growing my favorite indeterminate varieties, but I'm also going to be trying out these 4 determinate ones:

Al Kuffa

Mountain Princess

Gold Nugget

Subarctic Plenty

We'll see how they perform!

Anyone with experience with determinate tomatoes? If so, please leave a comment with your thoughts, and any varieties you'd suggest or warn against.

Because of this, my tomatoes always end up sprawling in a tangled mess on the ground. I know they'll be healthier if I stake. I know it will be easier to harvest them if I stake. Because I know this, some years I actually go so far as to put stakes out in the garden, which resulted in my tomatoes being a wild mess with some stakes sticking out of the middle.

So this year, I'm going to try growing some determinate tomatoes.

The technical definitions of determinate and indeterminate just refer to where flowers are produced. Determinate plants produce them at the top of a stem, forcing new growth to come from new branches at the side of the plant, while indeterminate plants produce flowers along the sides of the stem, allowing a single branch to keep growing on and on and on.

This means that determinate tomatoes grow short and bushy -- rarely needing to be staked -- while indeterminate tomatoes grow long and floppy -- and theoretically ought to be staked, though of course I never actually do.

I've steered away from indeterminate tomatoes up until now, though, because catalogs always define them a different way: They say the determinate tomatoes produce fruit which ripens all at once, while indeterminate varieties produce continuously all summer long.

But: Recently I've been reading something different: Tom Clothier on the tomato page of his quirky, very enjoyable website, says some there are determinate tomatoes, which produce a load of fruit and then stop, and there are vigorous or strong determinates, which keep sending up new shoots, ending in flowers and fruit, all season -- so they produce continously like a indeterminate, but minus the staking, and are usually much earlier than indeterminates.

Which sounds perfect to me... We'll see! If I can get tomatoes which produce well and taste yummy but don't turn themselves into a tangled mass, I'm all for it. I'm still growing my favorite indeterminate varieties, but I'm also going to be trying out these 4 determinate ones:

Al Kuffa

Mountain Princess

Gold Nugget

Subarctic Plenty

We'll see how they perform!

Anyone with experience with determinate tomatoes? If so, please leave a comment with your thoughts, and any varieties you'd suggest or warn against.

08 January 2010

Drawing: Road trips with gardeners

My friend, the beautiful and brilliant Virginia recently started a blog and posted about an up coming trip to longwood gardens. ...which brought to mind an earlier road trip she told me about involving a small car, a large palm tree, and a LONG drive... And inspired this drawing:

See my other gardening drawings

06 January 2010

Wednesday Links

After taking a week off for Christmas, Wednesday links is back!

First, a post from Dirt Simple with a really cool idea: Giant votive candle holders made from ice for an incredible fire-and-ice display outside. I'm going to have to try this one. Nothing is blooming outside, so might as well use the cold to make something beautiful!

The economist reports on the potential to use a species of dandelion to make rubber which I pass on only because it feels like a kind of validation for my recent excitement over dandelions.

Check out this cool time lapse photography of the garden over at Ellis Hollow. It is the entire year in 100 seconds. I think I have to add doing this to my list of garden resolutions for 2010.

Order your seeds early this year! The Baltimore Sun thinks there might be a seed shortage for 2010.

Another british newspaper makes me jealous by published a retrospective of the decade in gardening trends. My hope for the coming decade is that gardening will catch on in the US to the point where we can discuss gardening celebrities and design trends the same way.

I want this.

First, a post from Dirt Simple with a really cool idea: Giant votive candle holders made from ice for an incredible fire-and-ice display outside. I'm going to have to try this one. Nothing is blooming outside, so might as well use the cold to make something beautiful!

The economist reports on the potential to use a species of dandelion to make rubber which I pass on only because it feels like a kind of validation for my recent excitement over dandelions.

Check out this cool time lapse photography of the garden over at Ellis Hollow. It is the entire year in 100 seconds. I think I have to add doing this to my list of garden resolutions for 2010.

Order your seeds early this year! The Baltimore Sun thinks there might be a seed shortage for 2010.

Another british newspaper makes me jealous by published a retrospective of the decade in gardening trends. My hope for the coming decade is that gardening will catch on in the US to the point where we can discuss gardening celebrities and design trends the same way.

I want this.

05 January 2010

Anyone want to grow some crazy mixed-up tomato hybrid F2s?

Two years ago I crossbred the tomato Matt's Wild Cherry (which is simply the most delicious cherry tomato I have EVER had the pleasure of eating) with Black Krim (which is a tasty, large, dark colored variety ) Last year I grew the F1 plants, and collected a LOT of F2 seed (See my post yesterday for an explanation of the F1 F2 stuff) which I am going to be growing this year: They will be a crazy mix of sizes (roughly ¾ will be cherries, ¼ full sized, though there should be a lot of size variation within those two groups), colors, and flavors – though all of them should be very delicious. I'm looking forward to growing out lots and lots, tasting them, and picking out my favorites – and I'm wondering it anyone else wants to do so as well. I've got oodles of seed, so if you want to grow some, just e-mail me (engeizuki at gmail dot com) and I can send them to you. All I ask is that you grow a bunch of plants, do a taste test, and send me back some seeds from any individuals you particularly like.

Two years ago I crossbred the tomato Matt's Wild Cherry (which is simply the most delicious cherry tomato I have EVER had the pleasure of eating) with Black Krim (which is a tasty, large, dark colored variety ) Last year I grew the F1 plants, and collected a LOT of F2 seed (See my post yesterday for an explanation of the F1 F2 stuff) which I am going to be growing this year: They will be a crazy mix of sizes (roughly ¾ will be cherries, ¼ full sized, though there should be a lot of size variation within those two groups), colors, and flavors – though all of them should be very delicious. I'm looking forward to growing out lots and lots, tasting them, and picking out my favorites – and I'm wondering it anyone else wants to do so as well. I've got oodles of seed, so if you want to grow some, just e-mail me (engeizuki at gmail dot com) and I can send them to you. All I ask is that you grow a bunch of plants, do a taste test, and send me back some seeds from any individuals you particularly like.Photo credits:

Matt's wild cherry

Black Krim

04 January 2010

What the F?

Welcome to my explanation of the terms F1 and F2. I'm writing this in preparation for a future post in which I want to reference these terms -- I don't want to have to explain them in that post, and I think most people know roughly what they mean, but just in case, I'm writing this so I can link back to it for the sake of the confused

.

When you make a hybrid between two different varieties or species or whatevers the first generation is the F1 generation. The babies of the F1s are the F2s, children of the F2s are the F3s, et cetera.

One talks about F1s and F2s a lot because they have special characteristics, which basically boil down to this: If I cross two different things, the F1s will all be the same, and the F2s will all be different.

Some real life pictures of this: For my research in grad school, I'm working with a hybrid of two species of petunia: Petunia axillaris, which is white, and the red flowered Petunia exserta.

The F1 generation of this hybrid all looks the same: Very, very pale pink flowers:

While a bunch of F2 plants look like this: A random mix of all different shades of pink.

But WHY are the F1s all the same, and the F2s all different? Let me use another example: A couple years ago I made a hybrid between two tomatoes. One, Matt's Wild Cherry is (as you might guess...) a cherry tomato. The other, Black Krim, is not a cherry tomato. The cherry trait is controlled by a single gene: Have one or more copies of the dominate version (C) of this gene, and you make cherry tomatoes. Have two copies of the recessive version (c) and you make big fruits. So I made my two tomatoes have sex, and they had a bunch of little F1 babies. Each F1 got a copy of each gene from each of the parents. From Matt's Wild Cherry they got the dominate version C, and from Black Krim, the recessive version c. So all the F1 plants had one C and one c, and since C is dominate, they were all cherry tomatoes. I then crossed the different F1 plants with each other to produce the F2 generation. Now each F1 has one copy of C and one of c, so when they make babies, they randomly choose just one of the versions of the gene (sometimes C, sometimes c) to pass on to the next generation -- meaning among the F2 plants, some will happen to get a C from both parents, some will get one C and one c, and some two copies of c – making the F2 generation a mix of cherry and full sized tomatoes.

The exact same process works for all the other genes in the tomato: There are genes for the dark color of Black Krim, genes for the sweetness and flavor of their fruit, how they grow, when they flower, and so on. All the F1 plants are the same with exactly one version of each gene from each parent, but the F2 will be a wild mix of all the different possible combinations of the different genes from the two parents.

And why should you care? Well, seed companies use this all the time to their advantage. When they are developing a new variety of tomato, they need it to be uniform – all the seedlings need to look the same (if you buy a packet of Early Girl seeds, and some plants came out as cherries, and others yellow, you wouldn't be too pleased, now would you?) The easiest way to make a variety uniform is inbreeding: Cross closely related plants each generation and you'll eliminate genetic variation resulting in perfect uniformity. But just as it isn't smart to marry your sister, inbred plants have problems (well, usually – some plants, like squash, are actually fine with it). So what to do? Well, if you take two uniform, inbred lines, and hybridize them the F1 generation will be not be inbred, because it is a hybrid, but will be uniform because it is a F1. Problem solved. And even better, if a company sells F1 hybrids, you have to buy new seeds every year because if you save your own seeds, they will produce the F2 generation when all chaos breaks loose. So F1 hybrid varieties are not only an easy way to make healthy, uniform varieties, they also are a good way to ensure repeat sales (Though to be honest, people saving seeds isn't much of a concern to seed companies – the bigger issue is other seed companies using their varieties to develop similar, competing varieties, something releasing F1 hybrids makes that much harder to do.)

So that's it, really: The numbers after the F indicate what generation you are talking about, and the ones we generally care about are the F1s, which are all the same, and F2s, which are all different. I hope you now feel extremely wise.

.

When you make a hybrid between two different varieties or species or whatevers the first generation is the F1 generation. The babies of the F1s are the F2s, children of the F2s are the F3s, et cetera.

One talks about F1s and F2s a lot because they have special characteristics, which basically boil down to this: If I cross two different things, the F1s will all be the same, and the F2s will all be different.

The F1 generation of this hybrid all looks the same: Very, very pale pink flowers:

While a bunch of F2 plants look like this: A random mix of all different shades of pink.

But WHY are the F1s all the same, and the F2s all different? Let me use another example: A couple years ago I made a hybrid between two tomatoes. One, Matt's Wild Cherry is (as you might guess...) a cherry tomato. The other, Black Krim, is not a cherry tomato. The cherry trait is controlled by a single gene: Have one or more copies of the dominate version (C) of this gene, and you make cherry tomatoes. Have two copies of the recessive version (c) and you make big fruits. So I made my two tomatoes have sex, and they had a bunch of little F1 babies. Each F1 got a copy of each gene from each of the parents. From Matt's Wild Cherry they got the dominate version C, and from Black Krim, the recessive version c. So all the F1 plants had one C and one c, and since C is dominate, they were all cherry tomatoes. I then crossed the different F1 plants with each other to produce the F2 generation. Now each F1 has one copy of C and one of c, so when they make babies, they randomly choose just one of the versions of the gene (sometimes C, sometimes c) to pass on to the next generation -- meaning among the F2 plants, some will happen to get a C from both parents, some will get one C and one c, and some two copies of c – making the F2 generation a mix of cherry and full sized tomatoes.

The exact same process works for all the other genes in the tomato: There are genes for the dark color of Black Krim, genes for the sweetness and flavor of their fruit, how they grow, when they flower, and so on. All the F1 plants are the same with exactly one version of each gene from each parent, but the F2 will be a wild mix of all the different possible combinations of the different genes from the two parents.

And why should you care? Well, seed companies use this all the time to their advantage. When they are developing a new variety of tomato, they need it to be uniform – all the seedlings need to look the same (if you buy a packet of Early Girl seeds, and some plants came out as cherries, and others yellow, you wouldn't be too pleased, now would you?) The easiest way to make a variety uniform is inbreeding: Cross closely related plants each generation and you'll eliminate genetic variation resulting in perfect uniformity. But just as it isn't smart to marry your sister, inbred plants have problems (well, usually – some plants, like squash, are actually fine with it). So what to do? Well, if you take two uniform, inbred lines, and hybridize them the F1 generation will be not be inbred, because it is a hybrid, but will be uniform because it is a F1. Problem solved. And even better, if a company sells F1 hybrids, you have to buy new seeds every year because if you save your own seeds, they will produce the F2 generation when all chaos breaks loose. So F1 hybrid varieties are not only an easy way to make healthy, uniform varieties, they also are a good way to ensure repeat sales (Though to be honest, people saving seeds isn't much of a concern to seed companies – the bigger issue is other seed companies using their varieties to develop similar, competing varieties, something releasing F1 hybrids makes that much harder to do.)

So that's it, really: The numbers after the F indicate what generation you are talking about, and the ones we generally care about are the F1s, which are all the same, and F2s, which are all different. I hope you now feel extremely wise.

02 January 2010

Genetic engineering: a statement of opinion

Partially inspired by my recent annoyance with a certain seed catalog, I've decided it is high time I wrote out some of my thoughts about genetic engineering. A long post, but I hope you'll take the time to read it and comment on it.

Genetic engineering is the process of taking a segment of DNA from one organism and popping it into the genome of another organism. Which sounds pretty radical, but actually isn't. Basically, that is what sex is: the genes from the two parents get mixed together into a new combination. Happens all the time, and humans have been manipulating these combinations of genes since before history. Bread wheat, for example, was created by combining the genes of three different species (Triticum urartu, Aegilops speltoides, and Aegilops tauschii) into one plant.

So genetic engineering isn't fundamentally different than what has been going on in this world since sex was invented (actually, before sex was invented: bacteria trade genes without sex all the time). It is basically the same process that converted wild almonds (which are toxic) into something you can eat and made the scrubby little plant teosinte into corn. You can take a gene from one potato and put it in other potato via traditional breeding or via genetic engineering and end up with exactly the same result. In short, there is nothing inherently dangerous or different about genetic engineering. It is basically the same thing as traditional breeding – only more powerful A lot more powerful.

I like to compare genetic engineering to the internet. The internet is powerful – you can do a LOT of different things with it. Good things like sharing information, and making friends, bad things like child pornography, and just silly things like funny cat videos. The internet isn't good or bad – it is just a powerful tool people use in different ways. The same is true of genetic engineering. It isn't good or bad, it can just do a lot of different stuff: some of it good, some bad, and some just silly.

A couple examples to show what I mean:

Bt Corn and cotton: Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) is a soil bacteria which produces a protein lethal to caterpillars (in some strains – other strains are lethal to other specific groups of insects) but is entirely nontoxic to other organisms (like us). Bt is a wildly popular organic insecticide -- if you like to eat organic produce, you also eat large quantities of Bt. So, scientists took the gene for the Bt toxin out of the bacteria and popped it into other crops – most popularly, corn and cotton. Now instead of spraying synthetic insecticides, the plants produce their own organic insecticide right in their leaves. The short term impacts have been overwhelmingly positive. Cotton used to be THE most heavily sprayed crop in the world (followed closely by apples). Virtually all cotton now has the Bt gene, and the result has been a dramatic reduction in spraying, resulting in far fewer pesticide poisonings (particularly in places like India where a lot of cotton is grown with minimal safety regulations), a big uptick in the health wild insect populations, less CO2 production because fossil fuel burning tractors aren't having to drive out all the time to spray, and increased yields on less land so more wild areas can be left intact. Which is all terrific.

But there is cause for concern. What if, for example, Bt corn cross bred with its wild ancestor, teosinte, in Mexico and the gene moved out into wild populations? Suddenly, wild ecosystems would have an incredibly powerful new insecticidal gene floating around. What would happen to wild insect populations? Would teosinte become able to out compete other wild plants? Currently, you are not allowed to grow any genetically engineered crops in areas where their wild ancestors also grow to prevent accidental cross pollination – but how easy is that going to be to enforce? All it takes is one farmer in Southern Mexico with a handful of corn from the US, and the Bt gene could be out in wild populations.

In my view, the Bt gene is very powerful, and so far powerfully positive, but certainly has the potential to be dramatically negative.

Golden rice:

In some of the poorest parts of Asia, people rely on rice as a staple crop. They are barely able to feed themselves, and much of the year they eat virtually nothing but rice -- a problem because rice is basically just starch. It provides the calories to keep a person alive, but it doesn't have much in the way of vitamins. The result is that in many of these places vitamin A deficiencies are pandemic. The World Health Organization estimates 250 million children are vitamin A deficient, some so severely that between 250,000 and 500,000 go blind each year -- and half of those die within a year of loosing their sight (Citation). Pretty sobering numbers. Enter golden rice – rice genetically engineered to produce vitamin a in the form of beta-carotene (which makes the grain yellow – hence the name). Distribute the golden rice seeds in these communities, and this debilitating vitamin deficiency could be a thing of the past, while keeping the people their independence. It requires no reliance on the gifts of food or vitamins from wealthier countries, rather provides them the tools to pull themselves out of a terrible situation. The downsides are... well, nothing. Producing beta-carotene in seeds doesn't do anything good for the rice, so even if it crossed with wild rice, the gene wouldn't persist in the wild, nor disrupt natural ecosystems. It would just save lives and end some suffering. Unfortunately, though the technology is up and ready to go, golden rice has never made it to the people who need it -- thanks to aggressive lobbying by well-fed environmentalists in the US and Europe.

There are lots of other things that are being done with genetic engineering: insulin and human growth hormone are both produced by genetic engineered bacteria, to dramatic effect for diabetics (good) and doping in sports (not so good). The Gates Foundation is funding an incredible project remaking cassava to transform – and save – the lives of people in sub-Saharan Africa. There are also goofy things like putting petunia genes into roses and carnations to try and make them blue – though really they come out sort of mauve-ish. Not bad, not good, just silly.

My point in all these examples is this: Debates about if genetic engineering, as a whole, is good or bad miss the point. It isn't good or bad, it is just powerful. What we need to be debating are the specifics: Is Bt corn worth the risks? Should we try and produce more nutrient supplemented crops like golden rice? Do we really need blue-ish roses? Because genetic engineering can be such a powerful force for good, we morally can't just shut down the debate because it sounds strange or “unnatural.” Those might be sufficient reasons to not make blue roses – but not sufficient to keep things like golden rice out of the hands of malnourished people. We need a healthy, informed discussion of genetic engineering so we can harness its power to help people, and avoid using it to do things we'll regret.

Photo credits:

Teosinte and corn

Golden rice

Genetic engineering is the process of taking a segment of DNA from one organism and popping it into the genome of another organism. Which sounds pretty radical, but actually isn't. Basically, that is what sex is: the genes from the two parents get mixed together into a new combination. Happens all the time, and humans have been manipulating these combinations of genes since before history. Bread wheat, for example, was created by combining the genes of three different species (Triticum urartu, Aegilops speltoides, and Aegilops tauschii) into one plant.

So genetic engineering isn't fundamentally different than what has been going on in this world since sex was invented (actually, before sex was invented: bacteria trade genes without sex all the time). It is basically the same process that converted wild almonds (which are toxic) into something you can eat and made the scrubby little plant teosinte into corn. You can take a gene from one potato and put it in other potato via traditional breeding or via genetic engineering and end up with exactly the same result. In short, there is nothing inherently dangerous or different about genetic engineering. It is basically the same thing as traditional breeding – only more powerful A lot more powerful.

I like to compare genetic engineering to the internet. The internet is powerful – you can do a LOT of different things with it. Good things like sharing information, and making friends, bad things like child pornography, and just silly things like funny cat videos. The internet isn't good or bad – it is just a powerful tool people use in different ways. The same is true of genetic engineering. It isn't good or bad, it can just do a lot of different stuff: some of it good, some bad, and some just silly.

A couple examples to show what I mean:

Bt Corn and cotton: Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) is a soil bacteria which produces a protein lethal to caterpillars (in some strains – other strains are lethal to other specific groups of insects) but is entirely nontoxic to other organisms (like us). Bt is a wildly popular organic insecticide -- if you like to eat organic produce, you also eat large quantities of Bt. So, scientists took the gene for the Bt toxin out of the bacteria and popped it into other crops – most popularly, corn and cotton. Now instead of spraying synthetic insecticides, the plants produce their own organic insecticide right in their leaves. The short term impacts have been overwhelmingly positive. Cotton used to be THE most heavily sprayed crop in the world (followed closely by apples). Virtually all cotton now has the Bt gene, and the result has been a dramatic reduction in spraying, resulting in far fewer pesticide poisonings (particularly in places like India where a lot of cotton is grown with minimal safety regulations), a big uptick in the health wild insect populations, less CO2 production because fossil fuel burning tractors aren't having to drive out all the time to spray, and increased yields on less land so more wild areas can be left intact. Which is all terrific.

But there is cause for concern. What if, for example, Bt corn cross bred with its wild ancestor, teosinte, in Mexico and the gene moved out into wild populations? Suddenly, wild ecosystems would have an incredibly powerful new insecticidal gene floating around. What would happen to wild insect populations? Would teosinte become able to out compete other wild plants? Currently, you are not allowed to grow any genetically engineered crops in areas where their wild ancestors also grow to prevent accidental cross pollination – but how easy is that going to be to enforce? All it takes is one farmer in Southern Mexico with a handful of corn from the US, and the Bt gene could be out in wild populations.

In my view, the Bt gene is very powerful, and so far powerfully positive, but certainly has the potential to be dramatically negative.

Golden rice:

In some of the poorest parts of Asia, people rely on rice as a staple crop. They are barely able to feed themselves, and much of the year they eat virtually nothing but rice -- a problem because rice is basically just starch. It provides the calories to keep a person alive, but it doesn't have much in the way of vitamins. The result is that in many of these places vitamin A deficiencies are pandemic. The World Health Organization estimates 250 million children are vitamin A deficient, some so severely that between 250,000 and 500,000 go blind each year -- and half of those die within a year of loosing their sight (Citation). Pretty sobering numbers. Enter golden rice – rice genetically engineered to produce vitamin a in the form of beta-carotene (which makes the grain yellow – hence the name). Distribute the golden rice seeds in these communities, and this debilitating vitamin deficiency could be a thing of the past, while keeping the people their independence. It requires no reliance on the gifts of food or vitamins from wealthier countries, rather provides them the tools to pull themselves out of a terrible situation. The downsides are... well, nothing. Producing beta-carotene in seeds doesn't do anything good for the rice, so even if it crossed with wild rice, the gene wouldn't persist in the wild, nor disrupt natural ecosystems. It would just save lives and end some suffering. Unfortunately, though the technology is up and ready to go, golden rice has never made it to the people who need it -- thanks to aggressive lobbying by well-fed environmentalists in the US and Europe.

There are lots of other things that are being done with genetic engineering: insulin and human growth hormone are both produced by genetic engineered bacteria, to dramatic effect for diabetics (good) and doping in sports (not so good). The Gates Foundation is funding an incredible project remaking cassava to transform – and save – the lives of people in sub-Saharan Africa. There are also goofy things like putting petunia genes into roses and carnations to try and make them blue – though really they come out sort of mauve-ish. Not bad, not good, just silly.

My point in all these examples is this: Debates about if genetic engineering, as a whole, is good or bad miss the point. It isn't good or bad, it is just powerful. What we need to be debating are the specifics: Is Bt corn worth the risks? Should we try and produce more nutrient supplemented crops like golden rice? Do we really need blue-ish roses? Because genetic engineering can be such a powerful force for good, we morally can't just shut down the debate because it sounds strange or “unnatural.” Those might be sufficient reasons to not make blue roses – but not sufficient to keep things like golden rice out of the hands of malnourished people. We need a healthy, informed discussion of genetic engineering so we can harness its power to help people, and avoid using it to do things we'll regret.

Photo credits:

Teosinte and corn

Golden rice